by Daniel Long, Nottingham Trent University

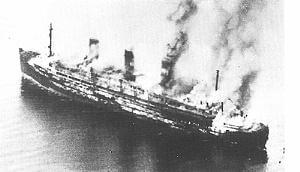

On the afternoon of May 3, 1945, a squadron of RAF Typhoons began their descent to attack Axis shipping in Neustadt Bay, Germany. Below them, the former luxury liner SS Cap Arcona was laden with over 4,500 concentration camp prisoners who had been “evacuated” to the coast – and at around 3pm, the Typhoons from the Second Tactical Air Force, launched their assault.

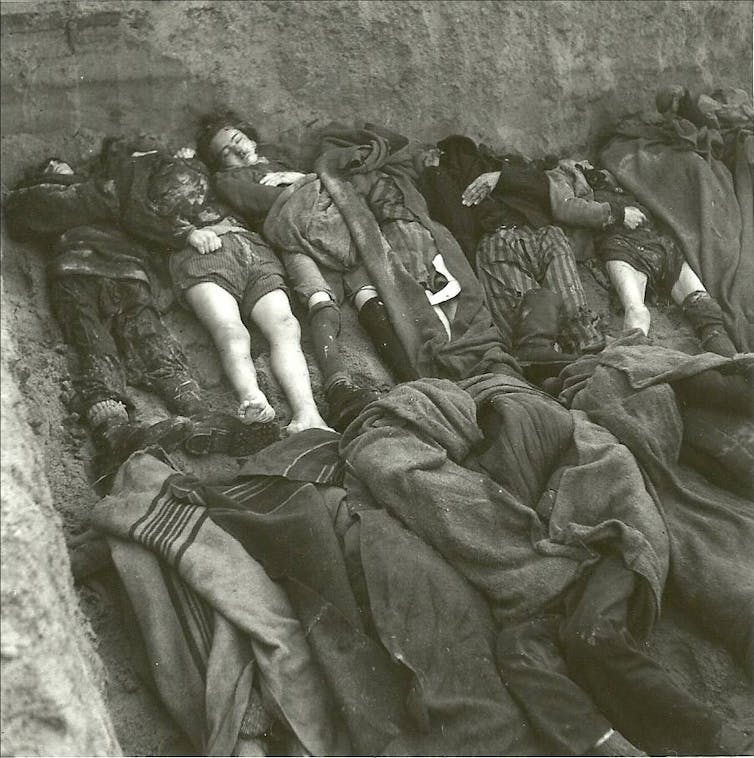

The result was one of the world’s worst maritime disasters, leaving the prisoners and the ship’s crew struggling for survival in the icy Baltic waters. An estimated 4,000 prisoners perished. More than 70 years on from the tragic sinking, crucial questions remain regarding the role of British forces in the final days of the Second World War.

The disaster has long been sensationalised by the print media. Headlines such as “Friendly fires of hell” have been the norm – thanks, in part, to a surprising lack of scholarly attention.

The Cap Arcona in 1927. Wikipedia

In turn, this has led to a number of conspiracy theories about the sinking. One such rumour claimed that important British records related to the incident had been sealed until 2045. In fact, all of the records were publicly released in 1972 after the Public Records Act 1967 reduced the amount of time they were to be kept secret – and I have spent a great deal of time researching them.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, Britain’s focus was on attempting to prosecute Nazi war criminals, and investigations into British misadventures were sidelined. And shortly after that, attentions shifted east, as the Cold War gathered pace.

Nevertheless, it is now possible to reconstruct what really happened – including Britain’s role in the tragedy – with a closer examination of archival files.

Endgame

“No concentration camp prisoner must fall alive into enemy hands.”

That was Himmler’s last order concerning the fate of Germany’s remaining camp prisoners. But as the Nazi camp system continued to contract in March 1945, it would be wrong to assume that it was the real driving force behind the evacuation of Neuengamme camp.

Neuengamme, near Hamburg, was largely unique within the Nazi camp system. Local politicians, in particular Nazi Gauleiter Karl Kaufmann, had developed close business links with local industrialists and supplying slave labour from the camp to nearby businesses became a profitable enterprise.

But by early 1945, the Allied advance placed increasing pressure on local politicians – and complicit businesses – to eradicate any evidence of slave labour from within Hamburg city limits. The “problem” had to be moved elsewhere.

Karl Kaufmann. Bundesarchiv Bild via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

In the absence of another option, Kaufmann made arrangements in March 1945 to requisition a passenger liner to act as a “temporary” holding camp for Neuengamme’s prisoners. Any long-term planning was simply nonexistent. Indeed, once the camp was emptied in mid-April, the local politicians no longer concerned themselves with the fate of the prisoners now held in squalor aboard the Cap Arcona in nearby Neustadt Bay.

Nevertheless, the “prisoner hierarchy” continued on board the ship. The prisoners remained segregated according to nationality and religion. In addition, SS troops stayed on board to supervise the prisoners. This indicated that the Arcona was intended as a temporary extension of the original Neuengamme, albeit one that was largely out of sight and out of mind.

Liberation or destruction

Following the Allied Yalta Conference of February 1945, British military policy was geared towards a swift advance to the Baltic coast.

There were two reasons for this. First, Britain wished to halt the Soviet advance as it swept ever further west. To achieve this, Lübeck on the Baltic coast was considered the strategic goal.

Second, by halting the Soviets here, British forces would be able to liberate Denmark and restore the Danish monarchy. With the monarchy restored, Britain would gain a valuable ally in the months ahead.

But the speed of the Soviet advance meant that the normal protocols and procedures that had been well established throughout the war fell to the wayside as British troops raced for their objective. To make matters worse, communication lines became strained, and intelligence was not always processed in a thorough and timely manner.

Casualties of the tragedy. Imperial War Museum Image Collection

On the afternoon of May 2 and the morning of May 3, two pieces of intelligence were handed to British commanders. The first was handed to the liberating forces of Lübeck, the 11th Armoured Division, by an International Committee Red Cross delegate (ICRC). The second was presented to British forces by a Swedish Red Cross (SRC) delegate.

Both informed the British that camp prisoners were being held aboard ships in Neustadt Bay. But the warning arrived too late.

As the German Reich contracted, British forces remained heavily engaged in an important battle to reach their objective on Germany’s north coast. But while the German retreat was often marked by disorder, Britain’s military campaign also became frantic and chaotic, particularly in the final weeks. A breakdown of efficient communication and intelligence sharing meant that frontline forces were often ill-prepared for the actual situation ahead of them.

Cap Arcona Memorial, Neustadt. Author provided

In this case, the latest intelligence on the ships in Neustadt Bay never reached the pilots who attacked them. As they made their final descent, the airmen likely believed they were attacking bona fide hostile targets.

![]() Ultimately, the fate of the Cap Arcona and its passengers was a tragic consequence of the fog of war.

Ultimately, the fate of the Cap Arcona and its passengers was a tragic consequence of the fog of war.

Daniel Long, PhD Candidate, School of Art and Humanities, Nottingham Trent University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.