COURGcrew —

TL;DR

- All systems go for first wave deployment beginning of December

- Dial, hand, and case manufacturing walk-throughs.

- Many people work hard to build your COURG — in these 3 areas alone, a minimum of 15 craftspeople.

Here’s a Thanksgiving edition update. I’ll blast this out to everyone since it’s been a bit of a radio silence since our last debrief. But the next 3 trip debriefs I’ll summarize before the next blast.

Apologies for going MIA for a week. I planned to file these dispatches in real-time each day, but we took some enemy flak in the form of the Great Firewall of China, some food poisoning (I blame seafood), and a cold. And then I didn’t realize that all work shuts down for 1.5 hrs each day for lunch and siesta.

In some cases, workers stayed at it and let me see the workflow so I could move on to the next stop on time. The workshops and factories were scattered across the industrial outskirts so everything was an hour apart, and then we also contended with traffic bottlenecks at almost every turn.

The trip was an eye opener and really humbling to see how many people must work in tandem in order to craft the COURG for us. I have new-found respect for the men and women who help make the COURG. They are tireless in the attention to detail and stringent in producing excellent watch components.

As I toured these workshops and factories I saw many other big name brand watches on parallel production lines. We benefit from the stringent policies and standards that the larger established brands adhere to. For example, one brand insists on 5-day work weeks (other factories open 6 days), with hefty overtime.

Please know that this is a rough outline to give us a sense of the production. There are many other steps left out. The first day was jam-packed. We started around 8:30a and didn’t wrap at the titanium grade 2 factory until after the workers had already left for the day around 8p. What follows is a chronological account so you see as I saw, with some tidbits gleaned from later in the week for context.

So, this is quite long. Grab your favorite brew, sit back and enjoy the flight. Welcome to the hangar.

Crafting the Dial: Thankful for Precision

This machine stamps the dial out from the sheet.

Each dial then passes under the next machine to punch out the circular date window.

In order for the dial to sit properly in the movement, the worker at this station attaches two tiny legs to each dial.

Each dial must be water polished in order to smooth out the face so the paint will be smooth and to deburr raw edges.

Workers have special programmable machines that paint dials automatically. This is not it.

Turns out shiny dials are much easier to make. The COURG has a very matte dial.

This requires personal handling to ensure an extremely even coating.

These matte dials also have another added step that shinier dials don’t.

Matte dials must air dry before they go in the oven or the surface can develop flaws.

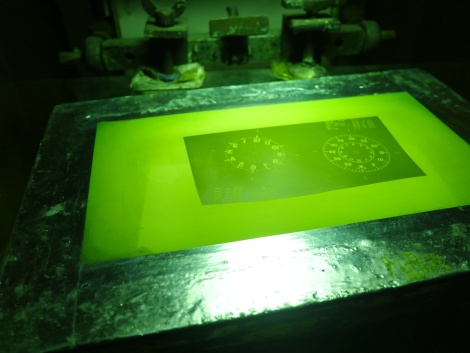

Once dry, it’s time for workers to paint each variant design. Here, screens bake under a hot light in preparation for paint and lume. The light burns away the dial design to allow paint through.

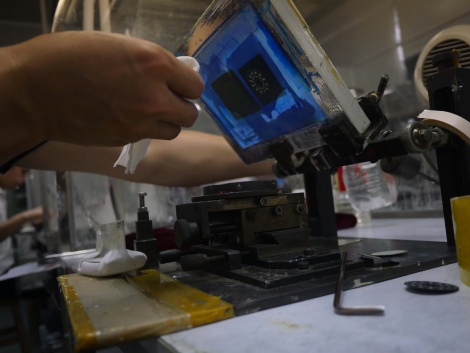

Here’s the setup for how the worker installs the screen.

The dial maker must line up dials with absolute precision for each layer to keep the lines clean. This is a tedious process of trial and error — adjust, test, adjust, test. Then bake dry. And he or she needs to do this 7 times — for each dial. Sometimes, mid-adjustment, the screen will rip. And he’ll have to start all over again. These artisans have 10 years of experience.

And it’s not enough just to layer the lume. The final step is baking the dials so they dry correctly. But they can’t bake too long or the color will be off from our vintage white. Remember: One manufacturer makes the dials and a completely separate manufacturer makes the hands. So they need to work together in tandem to ensure that the hands match. For COURG, they have to stop the baking process early and then let the dials finish drying at room temperature in a dust-free case or they get too yellow.

Hand Makers: Thankful for Generosity

The images you see here are pretty rare. The art of crafting watch hands is a closely guarded secret. I heard this during my design phase and again from our operatives as we started production. Initially, I was told I wouldn’t be allowed to visit. Our field agents worked hard to persuade them to open their doors for me.

Finally, the day I touched down, they relented. I could visit but was not allowed to take pictures or video. In fact, my itinerary actually had something to the effect of: Caution, do not photo or video here. However, once we infiltrated the premises, our field agents figured it wouldn’t hurt to ask again.

And BOOM:

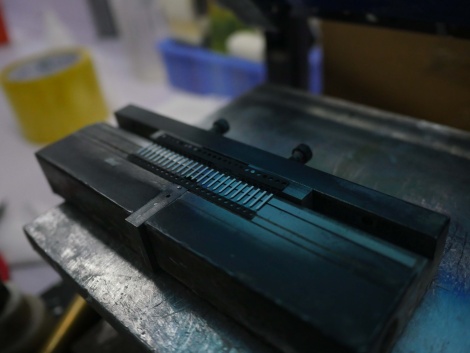

This machine grinds down molds and blades used for stamping the hands.

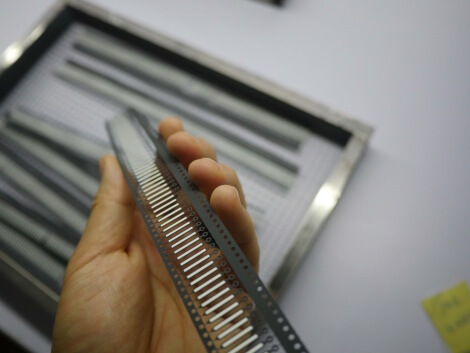

The sheets of brass that they use for the hands are ridiculously thin — like sheets of paper.

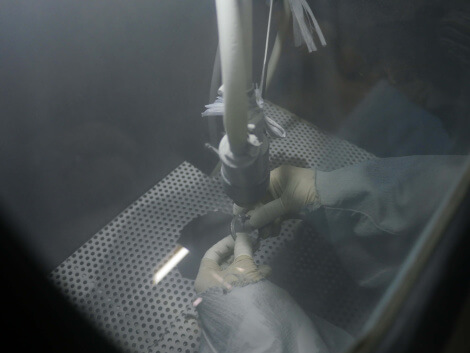

Here again, the works hand spray that matte black initial layer. And then the lume is hand-applied to each one with a tiny implement that bears a striking resemblance to a toothpick with a small paddle on one end.

After the hands dry in a similar process to the dials, a machine splices the hands from the holders. At this point, workers then inspect each and every hand to ensure quality finish. At one point the factory manager handed me a ziplock of rejected hands. I couldn’t tell what was wrong with them! Sometimes it’s a speck of dust. Sometimes the lume isn’t even.

Machining the Case: Thankful for Persistence

These are shots from the titanium grade 2 factory. Most steps for case refinement are similar between grade 2 and grade 5. Note that there are many steps before we get to this point. In fact there’s a whole other factory that casts the molds and produces the first COURG shape. They refer to the rough first titanium form that emerges from the mold as an “embryo.” Details on those operations come in a few days. Here’s the rough grinder.

After the final case shapes merge, each case earns its drilled lugs. Here’s one example of a big difference between the grade 2 and grade 5, which adds to costs, manufacturer headaches, and scares a lot of brands away from full TiGr5 cases. TiGr2 drills relatively easily. TiGr5 easily doubles if not triples the time per piece required to drill through. That’s because the drill bits get so hot that the maker needs to stop to let the metal cool. Instead of one pass per lug, each lug takes 6 or 7 passes. Not only that, they need to use diamond-tipped drill bits. And still, the bits often snap. As you can imagine, in an assembly-line type system this creates some serious bottlenecks.

This is where the stealthy matte magic happens: Sandblast!

QC. Rejects get marked and sent back for machining or grinding. Often they pulled cases for problems I would have never spotted. Those that pass inspection dunk in a warm mild detergent bath and then immediately go into a dryer.

Hope you and your families have a joyful and festive Thanksgiving!

Godspeed, elbert. Over and out —